School was finally out, which meant it was time for their trip to Grandma’s beach house, the sun-faded, yellow cottage where summer had always lived. Molly June’s mother had spent her own girlhood here, rinsing salt water and sand from her hair in the same outdoor shower. Molly continued her mother’s childhood, and had been coming since before she could walk, before she had words for how the air smelled like ocean and Coppertone and something that felt like happiness.

The house was like an old friend to her, the hammock on the porch with its pull-string to make it sway without getting up, the hall closet full of board games that smelled like musty cardboard and well-used time, and most importantly, the pool.

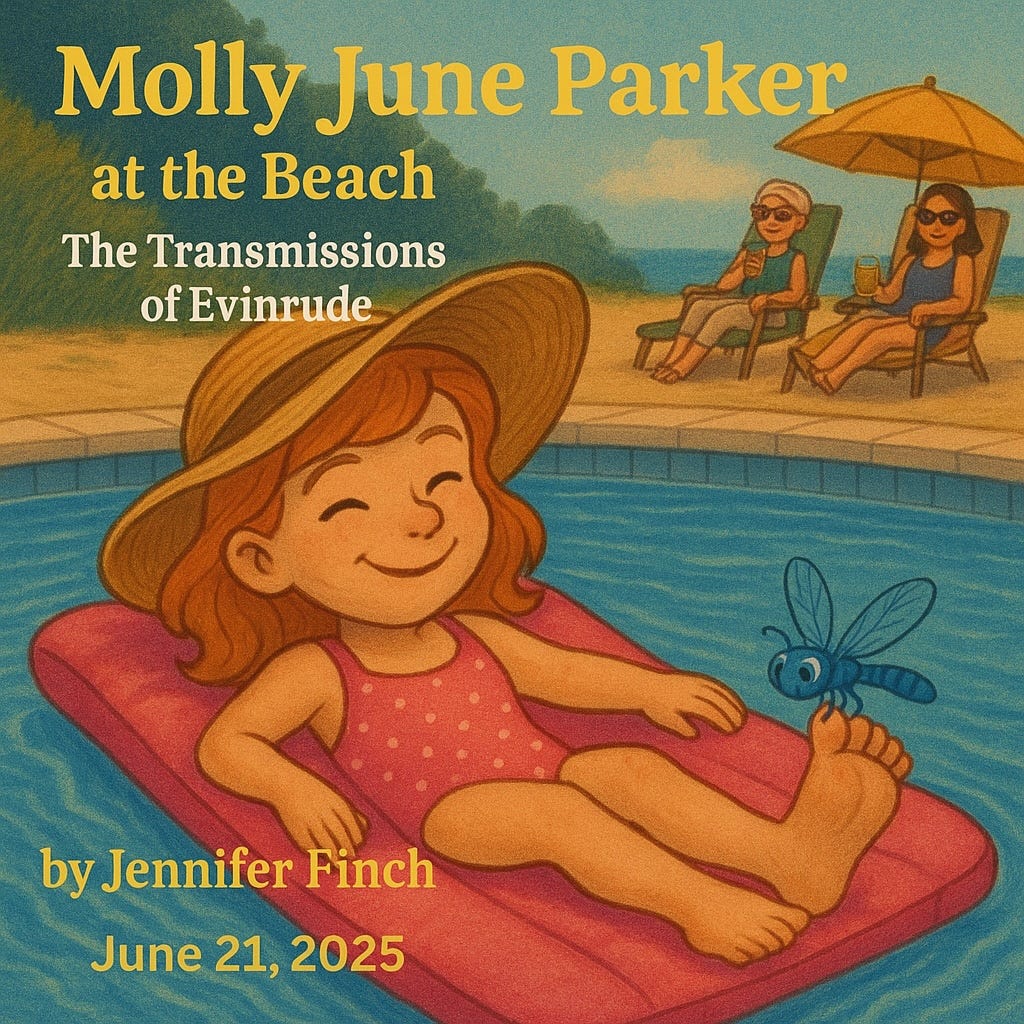

Molly June Parker was a serious floater. At eight-and-three-quarters years old, she had perfected the sacred summertime art of belly-up pool drift, arms flopped like boiled spaghetti, sun hat tilting just so over one brow. She was not the kind of girl who needed a pool noodle or a conversation. Her raft, a faded neon pink rectangle with a slow leak, was her throne. It made a soft pfft, as if it too was tired from trying so hard all year to save the first grade from bad and unruly leprechauns.

The sky above her was the kind of hot, humming blue that made even time lie down and take a nap. Somewhere beyond the dune fences, gulls squabbled over someone’s dropped sandwich crumbs. The air smelled of warm, slightly melting vinyl and sunscreen. And there she was, queen of all things chlorinated, Molly June Parker of no fixed schedule and little regard for adult rules like “reapply” or “hydrate.”

And then, he arrived.

He zipped in, a blue dragonfly the size of her thumb. He looked mechanical, almost, like something made by someone who’d once seen a dragonfly described but never met one personally. His wings shimmered with tiny stained-glass windows of greens and silvers and periwinkle-blues that seemed to blink in Morse code.

He landed on her big toe, the left one, which was painted pink. Or, more accurately, had been painted pink before salt and sand and a misguided attempt to dig a tunnel to China this morning wore the polish down to a weathered suggestion of its former self.

Molly June gasped in glee and didn’t move. She’d seen The Rescuers more times than she could count on two hands and one foot, and she knew a sign when she saw one.

“Evinrude?” she whispered.

The dragonfly twitched his head, as if to nod. Molly June sang, “R-E-S-C-U-E, Rescue Aid Society.” “Why are you here, Evinrude? Is someone in trouble? Do Bernard and Bianca need my help? Where’s Penny?”

And then, everything changed.

The pool rippled into translucence and shivered like it had goosebumps and started to churn rainbows through the water. Then the edges of the pool melted away and were replaced by a prismatic canyon. The cement tiles surrounding the pool transformed into shifting layers of opal and turquoise, like the skin of an oily fish.

Molly June’s raft bobbled in midair, face up and no longer in a pool, but in a canyon full of glass-bright rivers and floating islands threaded with ferns the size of patio umbrellas. The air sang. Singing in a language she didn’t know, but felt she’d understood once, maybe in a dream.

Evinrude’s wings flickered faster, igniting sparks, and then a hundred thousand wings, of countless Evinrudes, surrounded her with a warm greeting, whirring and fanning their wings like prostrated bows to her.

She felt so happy. This was so magical.

But as quickly as her unbounded joy set in, it vanished, and she began to grow a bit scared. The world below her, where she could see her mother and grandmother sipping Arnold Palmers by the poolside, was a hundred feet down, or a thousand, impossible to say. She clutched the pink raft, toes curled, as the raft dipped and began to drift on a current of air, or water, or nothing she could see. Evinrude sensed her panic and hopped off her toe.

The concrete returned. The sky simmered. The trees resumed their regular programming. Mom and Grandma sipped their afternoon refreshments and gossiped about nothing special.

Molly June sat up slowly, the raft wobbling beneath her. She was careful because she knew it had opinions about sudden movement. She scanned the pool deck. The world looked normal again. Almost flat, dull, ordinary, but safe.

Just to be sure, she called out, “Did you see that dragonfly? The blue one? He landed right on my toe.”

Her mom glanced over the rim of her sunglasses. “You mean Evinrude?” she asked, with a half-smile. “Yeah, I saw him zipping around. Pretty little guy.”

Grandma looked up and added, “They say dragonflies are lucky.” And then grandma gave a smile and a wink.

Molly June’s toes relaxed. She leaned back again, the raft giving a familiar pfft.

Lucky, she thought. That’s one way to put it.

Molly June Parker had always known about other worlds. She’d caught glimpses of them during math class, when the bad leprechauns would fog up the windows with their breath and trace cryptic little messages just for her. She’d have to shoo them away with her pencil eraser, pretending to concentrate while they giggled in the condensation.

Since before she could really even know, she was the kind of kid who tripped back and forth between realities like a loose shoelace, the kind of kid who got called into the principal’s office for acting out imaginary epic battles under her desk during social studies.

Her mother always believed her and said she was “sensitive to vibes,” which was grown-up code for “You are wonderful, and I love you just the way you are, and don’t let the world tell you any different.” Molly June loved her mom.

In kindergarten, she’d been the only one who could see the glittering, thumb-sized demons that lived in the cracks of the cafeteria floor, and when they tried to steal the teacher’s voice, she’d scared them off with a juice box and the threat of time-out. The faculty called her special. The principal knew her on a first-name basis. Her teachers said she had an “over-active imagination.” Molly June didn’t mind. She’d been to more places than most adults get to in a lifetime.

But this place, where she just went, wasn’t like any time before. This wasn’t a world that wanted something from her. There were no shadow imps that needed to be contained. No starfish-faced wolf cubs to be led back to their den in the janitor’s closet. This world was quiet. Rid of demons that needed to be tamed. Just beauty revealing itself and pulsing with luminosity.

And then it happened again. Evinrude landed, this time on her knee. And just like that, the world brightened. The colors got braver. The blue of the sky grew so vivid it almost glowed. The pool became a blue lagoon refracting turquoise and teal. The whole world turned into something more alive than she had ever seen, like a coloring book suddenly aware of its own outline. It’s as if a switch was toggled from “ordinary” to “hyper extraordinary.” A place where the world could be suddenly more of its own self than it had ever been.

Evinrude lifted off again, vanishing with the quick whirr of invisible gears. And the world flattened. Not completely, but like a dream that just popped after waking. Molly June tried to squeeze her eyes shut to get a few more drops of magic. But nothing happened. She blinked. She couldn’t get there on her own.

Evinrude didn’t just show her, he took her. With each landing, he tuned her like a radio dial, guiding her to a frequency she could finally see, feel, and hear.

And so it went—dragonfly on, world expands. Dragonfly gone, world shrinks.

She stopped trying to explain it by the third landing. Evinrude was not here to be explained. He was not here to follow logic or laws. He was here for her.

Later, when the sun had lowered itself to a friendlier angle and the pool cast long shadows across the water, Molly June climbed out, towel-draped and pruney. Her mom was inside, fixing dinner, the screen door clapping now and then like a homemade wind chime. But Grandma stayed outside, feet up, sipping the last of her Arnold Palmer with a crazy straw.

Molly padded over and sat cross-legged on the lounger beside her.

“Grandma,” she said quietly, almost like a test, “do dragonflies ever take you somewhere else?”

Grandma didn’t look surprised. She just smiled at the horizon like it had told her a good secret.

“When I was little,” she said, “I used to sit in that same pool and wait for them. One landed on my nose once. I thought it was trying to tell me something.”

Molly’s breath caught in her throat.

“They don’t just see this world,” Grandma went on, her voice soft and knowing. “They see the spaces between worlds. And if one chooses you, it means you’re ready to see them too.”

“They’ve always been messengers,” Grandma said softly. “In some places, they say dragonflies carry notes from the spirit world, little nudges from our ancestors, the ones who’ve loved us and stayed just out of sight. Your great-grandmother believed that. She used to say they come when you need reminding that you’re not alone.”

Molly swallowed. “I think he took me with him. Evinrude. Just for a second.”

Grandma smiled and reached over, brushing a strand of damp hair from Molly’s forehead. “I know my dear, you’re one of us, you always have been,” she said simply.

They sat in silence for a long moment, the kind that doesn’t need filling. And in that pause, something clicked into place. Molly June realized they both knew. Her mom, her grandma—they’d been there. They had felt the sky tilt and the trees breathe and the raft become a portal. They hadn’t forgotten. They had just grown quiet about it.

And now, they were handing the knowing down to her.

Molly looked at Grandma’s worn hands, the soft lines around her eyes, and felt something deeper than safety, bigger than words. It was the feeling of being seen exactly as you are, with nothing left out. It was being known by the people who raised you, all the way down to the secret places of your heart.

It was more than love. It was being seen and held in ancestral love. It was belonging.

Evinrude buzzed past them one more time, a flicker of sapphire in the warm dusk air.

Molly June smiled and whispered, “I see you, too.”